Eccosorb Filters in Quantum Computing Applications

The Advent of Quantum Mechanics – From de Broglie to Modern-Day

Quantum mechanics began to take shape 100 years ago, when Louis de Broglie proposed that all subatomic particles have an associated wave.1 In 1925, Erwin Schrödinger developed his wave equation for describing an electron, and one of his critics, Max Born, correctly claimed this equation “gave the probability that an electron would, when measured, be found at a particular point.1“ Werner Heisenberg recognized that if particles are described as waveforms instead of points, it is “mathematically impossible to calculate with precision both the position and momentum of a particle at a given point in time,” so in 1927 he developed the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.1 Further, in a subsequent stroke of genius, Schrödinger was the first to discuss quantum entanglement, conceptually and by name, in 1932.2

Quantum computing is a powerful, modern-day application of quantum mechanical principles. Quantum bits, or qubits, like classical bits, have two possible, measured states, 0 or 1.3 However, unlike their binary counterparts, qubits can exhibit a coherent superposition state and entanglement, and are subject to interference, making qubits “fundamentally different and much more powerful than classical bits.”3

In the field of quantum computing, absorptive Eccosorb® filters are essential for filtering out undesired thermal (IR) and microwave noise. In the paragraphs that follow, we define an Eccosorb filter and explore the physical design and construction of these filters using a cross sectional, cutaway view. Next, we delve into a quantum mechanical system that utilizes both traditional and Eccosorb filters, and discuss why the use of traditional filters alone is insufficient. Also, we describe the performance characteristics of Eccosorb filters at cryogenic temperatures and discuss why these characteristics lend themselves well to quantum mechanical systems.

Read on as we present a quantum mechanical system block diagram that shows how traditional and Eccosorb® filters are utilized in demanding, cryogenic environments in which quantum processors need to operate.

Eccosorb Filter Design and Construction

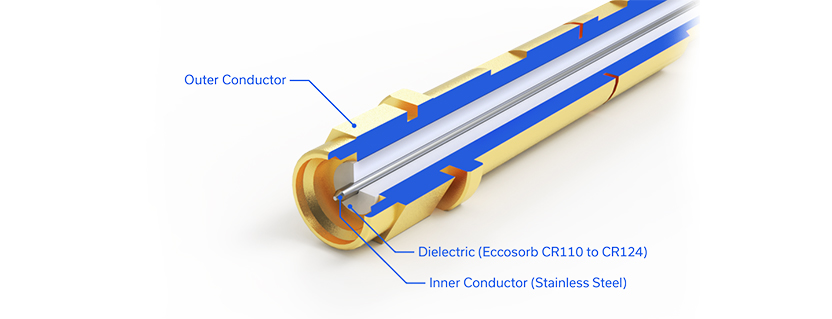

In short, Eccosorb® filters are a type of lossy-transmission-line filter, typically constructed in coaxial fashion, and often utilizing coaxial cable as a platform, in which a microwave-absorbing, magnetic particle-loaded dielectric is applied to achieve the desired frequency response and attenuation. Figure 1 shows an Eccosorb filter constructed from an RG402 (.141 semi-rigid) coaxial cable platform. These types of filters, as their name implies, are constructed with castable Eccosorb dielectric, commonly of the CR family, which ranges in magnetic particle concentration from lowest (CR-110) to highest (CR-124) density.4 Eccosorb was formerly designed and manufactured by Emerson & Cuming, and is now a product line of Laird™, a DuPont business.

Figure 1: Cross-sectional cutaway rendering of Mini-Circuits’ 43 mm Eccosorb CR-124 filter (left) and actual cross section (right).

For filters manufactured from coaxial cable, the Teflon® dielectric is often removed while the castable Eccosorb is vacuum outgassed to remove all the air, warmed to reduce viscosity, injected in place of the original dielectric, and cured.5 The center conductor is usually replaced by stainless steel, which is more robust than copper or brass.5 As an experienced competitor in the quantum computing market, Mini-Circuits designs and manufactures Eccosorb filters with proprietary techniques that make them well-suited to high-volume manufacturing. A radial cross-section of a Mini-Circuits’ Eccosorb filter is shown on the right in Figure 1.

Our proprietary techniques and capabilities enable Mini-Circuits to meet design-for-manufacturability (DFM) goals for any of the CR castable Eccosorb filter dielectrics. As an example of our capabilities, measurements for one of our many Eccosorb CR-124 filters are shown in a subsequent section.

Lumped Element and Eccosorb Filters in a Quantum Mechanical System

In 2021, H. Zhang, et. al. reported a significant reduction in qubit frequency “from GHz to MHz” in their fluxonium-based quantum processor, lowering the noise spectral density, yet still maintaining state of the art gate speeds.6 Their prominent experimental breakthrough utilized not only Eccosorb® filters, but a preponderance of Mini-Circuits’ traditional lumped element filters as shown in Figure 2.

The DC flux line is first filtered at room temperature (300K) with an RC low-pass filter with an fc of 0.1 Hz.7 This DC flux line filtering is not shown in Figure 1. On the left-hand side of Figure 2, the DC flux line undergoes 20 dB of attenuation in the still (700 mK) and subsequently passes through Mini-Circuits’ VLF-2350+ and SLP-1.9+ filters. To augment this traditional filtering, an Eccosorb filter (notionally based on CR-124, for purposes of discussion) is installed, followed by the Mini-Circuits’ ZFBT-4R2GW+ bias tee, in which the capacitor has been replaced with a short.

The RF flux input also undergoes attenuation, followed by traditional LC filtering that culminates with the Mini-Circuits’ VLF-2350+. Another Eccosorb filter, this time based on CR-110, is located inboard from the traditional filters and connected directly to the flux input of the fluxonium sample. A quick examination of the RF charge and RF output lines also reveals that CR-110 Eccosorb filters interface directly with the fluxonium sample as well. Next, we’ll discuss the rationale for applying cryogenically-cooled Eccosorb filters to the task of filtering noise directly at the quantum mechanical system interface.

Eccosorb Filters’ Importance to the Quantum Mechanical System

The fluxonium sample shown in the block diagram of Figure 26 is the quantum mechanical core, located in the mixing chamber (MC) at 15 mK. The fluxonium sample itself requires physical shielding from any form of radiation, including infrared, so the sample is physically enclosed in a lead shield. The sample must also be shielded from magnetism, hence the μ metal shield that houses the sample. Additionally, all input and output lines to and from the fluxonium quantum core must be protected from all types of radiation. This protection must be effective and consistent down to the noise photon level, and the frequency range must extend to the infrared band.8 While cryogenically-cooled attenuators and some of the traditional filters will reduce Johnson-Nyquist noise in the microwave region, the requirement that filtering be effective through mmWave and out to IR frequencies cannot be met by traditional filters.

Eccosorb® filters are often referred to as IR (infrared) filters because of their ability to filter out a spectrum of frequencies that extends to the IR spectrum, even when cooled to 15 mK. They also perform exceedingly well in quantum applications where filters adjacent to the quantum mechanical core must be absorptive and reflectionless. Eccosorb filters are well-matched in both the passband and the stopband, and exhibit excellent suppression from microwave through infrared.8

Performance Characteristics of Eccosorb Filters

Figures 3 and 4 show the frequency response of |S21| for a 50 mm long filter with an Eccosorb CR-110 dielectric and for a 43 mm Mini-Circuits’ filter with a CR-124 dielectric at room temperature. Both filters are based on an RG402 cable platform. The Mini-Circuits’ CR-124 filter has a 3 dB corner frequency of 470 MHz and the CR-110 filter an fc of 4.2 GHz. The corner frequency for the CR-110 filter is reported to increase by 50% between room temperature and 3K.8 The CR-124 filter -3 dB corner frequency is estimated to increase by 30%.8 A moving average was utilized to smooth the CR-110 filter data. While |S21| for the CR-110 filter ranges from approximately -25 to -40 dB between 20 and 67 GHz, the CR-124 filter, loaded with a much higher magnetic particle density, has a slope for |S21| between 2.5 and 5 GHz of the equivalent of a ten-section LC filter!

As a type of lossy-transmission-line filter, the 3 dB corner frequency of a given Eccosorb filter is determined by both its length and the loss-per-unit-length of the Eccosorb material that is utilized for the dielectric. As with any type of transmission line filter, the longer the filter body, the lower fc. As far as the Eccosorb dielectric materials go, the most heavily-loaded epoxy, CR-124 yields the lowest fc while the most lightly loaded CR110 allows for the highest corner frequency. In order of increasing density of magnetic particulate matter and decreasing corner frequency, the other Eccosorb blends are CR-112, CR-114, CR-116, and CR-117. Mini-Circuits’ volume manufacturing techniques for Eccosorb filters are robust and repeatable, and enable us to fabricate filters using any dielectric material, and achieve essentially void-free, reliable results.

The frequency response of |S11| and of |S22| is shown in Figure 5 for the Mini-Circuits’ CR-124 filter and |S22| alone is shown for the CR-110 filter,8 for which a moving average was used to smooth the data. The return loss is excellent for the CR-110 filter, long after the filter has rolled off by 20-30 dB. Even more striking is that long after the Mini-Circuit’ CR-124 filter has rolled off by over 80 to 100 dB the worst-case return loss is still 5-10 dB! This reflectionless behavior enables microwave and mmWave noise to be absorbed around the quantum core, and not reflected and subsequently reintroduced at another point in the quantum circuit.

Although |S21|, |S11| and |S22| data are only taken to 67 GHz, Masluk claims, in paragraph 4.6.1 of his 2012 dissertation that Emerson & Cuming expected the attenuation of their CR epoxy dielectrics to extend “fully into the optical region.”9 This is a critical reason why Eccosorb® filters find broad use in filtering noise in quantum computing applications, their ability to filter microwave, mmWave, infrared and even optical noise. The properties of CR-110 such as n, ε, and tan δ (loss tangent) were available at least as far back as 1997 for frequencies of 100, 300, and 900 GHz, and at temperatures of 4.8K and 300K (room).10

Eccosorb Filter Applications

By quickly looking back at Figure 2, we see that the CR-124 filter, with the lower cutoff frequency (fc of approximately 470 MHz at room temperature, and ~30% greater at cryogenic temperatures), is utilized on the DC flux line to filter out a broad spectrum of inbound noise. The CR-124 filter, in backing up the Mini-Circuits’ ZFBT-4R2GW+ bias tee inductor, is an excellent, absorptive backstop for any spectral content from the RF flux pulses that may run up the DC flux line and be reintroduced, or any noise in the hundreds of GHz to THz region that may come down the DC flux line. On the righthand side of Figure 2, a CR-110 filter is applied to the output (readout pulses) of the fluxonium sample, that emerge at approximately 7 GHz.7 The CR-110 filter is operating just beyond its cryogenic 3 dB cutoff frequency (fc(cryogenic) = fc(room) + 50% = 4.2 GHz + 50% = 6.3 GHz) for the 7 GHz readout pulses, so it is well suited to perform that low-pass function. Of equal importance is that the HEMT amplifier in the upper righthand corner of Figure 2 has a broad noise spectrum at its input, and any noise making its way through the low-pass filter and circulators is conveniently terminated by the absorptive nature of the CR-110 filter. Once again, the Eccosorb filter, in this case the CR-110 filter, serves to guard the quantum core against sources of noise that would otherwise alter the states of qubits and create significant readout errors.

Eccosorb Filters – From DC-to-Daylight

In this article the physical design and construction of Eccosorb® filters is described and a filter is illustrated using a cross sectional, cutaway view. Mini-Circuits’ design prowess and proprietary Eccosorb filter manufacturing techniques are discussed as well. We also show a quantum mechanical system that utilizes both reflective traditional filters and absorptive Eccosorb filters, and discuss why the use of traditional filters alone does not achieve the noise reduction required for quantum computing. We then turn our attention toward the performance characteristics of Eccosorb filters at cryogenic temperatures and discuss why these characteristics lend themselves well to quantum mechanical systems. Armed with a better understanding of Eccosorb filters, we return to Figure 2 to apply that knowledge to an actual quantum mechanical system, to fully appreciate the role Eccosorb filters play in the cryogenically-cooled, quantum mechanical world.

References:

- History of atomic theory – Wikipedia

- Erwin Schrödinger – Wikipedia

- What is a qubit? | Institute for Quantum Computing | University of Waterloo (uwaterloo.ca)

- Eccosorb™ CR (laird.com)

- Absorptive filters for quantum circuits: Efficient fabrication and cryogenic power handling | Applied Physics Letters | AIP Publishing

- Phys. Rev. X 11, 011010 (2021) – Universal Fast-Flux Control of a Coherent, Low-Frequency Qubit (aps.org)

- Fast control of low-frequency fluxonium qubits (stanford.edu)

- Engineering the microwave to infrared noise photon flux for superconducting quantum systems | EPJ Quantum Technology | Full Text (springeropen.com)

- Masluk-Nicholas-A.-Reducing-the-losses-of-the-fluxonium-artificial-atom-Yale-2012-1.pdf (bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com)

- Miscellaneous Data On Materials For Millimetre And Submillimetre Optics (terahertz.co.uk)

Courtesy of Mini-Circuits